Am I Working My Lower Back Too Much

We hope you enjoy reading this blog post. Ready to upgrade your body? Download the app

By Mofilo Team

Published

That dull, persistent ache in your lower back after deadlift or squat day is confusing. Is it the good kind of sore that means you're getting stronger, or is it a warning sign that something is about to go very wrong? It’s the question that keeps you up at night, worried you’re one bad rep away from a serious injury. You're not alone in this. Thousands of people feel this exact uncertainty, and it stalls their progress completely.

Key Takeaways

- Direct lower back exercises like hyperextensions should only be performed 1-2 times per week for 4-6 total sets.

- A dull, general ache that fades in 48-72 hours is normal muscle soreness; sharp, shooting, or radiating pain is an immediate stop signal.

- Your lower back is already worked heavily during compound lifts like squats and deadlifts, which counts as your primary volume.

- The number one cause of lower back strain is not over-training, but a weak core that fails to support the spine under load.

- If your form breaks down before you complete your target reps, the weight is too heavy and you are risking injury.

- Pain that travels down your leg or causes numbness is not muscle soreness and requires you to stop training that movement.

What's the Difference Between Soreness and Injury?

If you're asking, "am I working my lower back too much," you're trying to figure out if the feeling is productive muscle soreness or a destructive sign of injury. The fear is real, but the answer is usually straightforward once you know what to look for. Let's make it simple.

Productive muscle soreness, or Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS), feels like a dull, widespread ache. It might feel like your entire lower back is tight or fatigued, similar to how your legs feel after a hard squat session. It usually peaks 24 to 48 hours after your workout and then starts to fade. You'll notice it when you bend over to tie your shoes, but it's a general discomfort, not a sharp pain.

Injury pain is different. It's often sharp, stabbing, and localized. You can point to the exact spot that hurts. It might feel like a zap or an electric shock. A major red flag is radiating pain-discomfort that shoots down your glute or into your leg. Numbness or tingling are also serious warning signs. Unlike DOMS, which can feel better with light movement, injury pain often gets worse.

Here is the simple rule: If the pain is sharp, shooting, or travels, stop immediately. That is your body's emergency brake. If it's a dull, general ache that goes away within 3 days, that's just the price of getting stronger. Understanding this difference is the first step to training hard without fear.

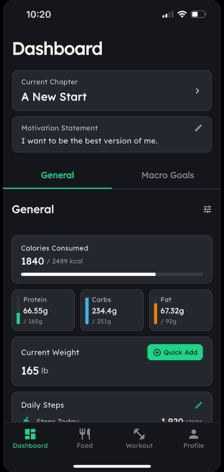

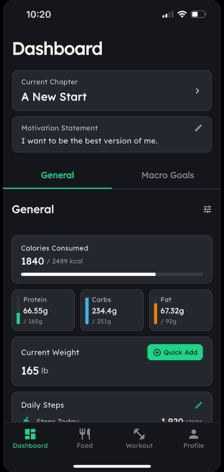

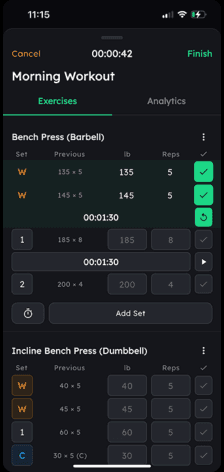

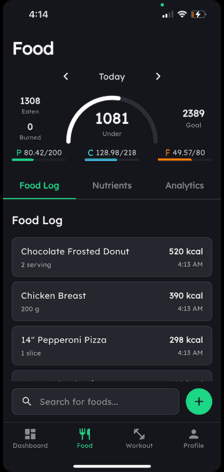

Stop guessing if your back is safe.

Track your lifts and volume. Know exactly how much you're doing.

Available on iOS and Android

Why "Just Resting" Doesn't Fix the Problem

When your lower back acts up, the most common advice you'll get is to just rest it for a week. So you do. You skip your deadlifts, avoid squats, and take it easy. The pain goes away, and you think the problem is solved.

Then you go back to the gym, load up the bar, and within a few reps, that familiar twinge returns. Why? Because resting only addresses the symptom (the pain), not the root cause.

The problem isn't that your lower back was tired. The problem is that it was being asked to do a job it wasn't prepared for. The true culprits are almost always one of these three things:

- A Weak Core: Your core isn't just your six-pack. It's a 360-degree belt of muscle, including your abs, obliques, and lower back (erector spinae). When your abs and obliques are weak, your lower back has to overcompensate to keep your spine stable, leading to strain.

- Improper Bracing: Many lifters think "keep your back straight" is enough. It's not. You need to create intra-abdominal pressure by actively bracing your entire core. Without this internal stiffness, the force of the lift goes directly onto your spinal discs.

- Excessive Direct Volume: You forget that heavy squats, rows, and overhead presses already hammer your lower back. Then you add 10 sets of good mornings and hyperextensions on top of that. It's like working your chest on Monday and then doing 10 more sets of flyes on Tuesday. It's simply too much direct work on top of the indirect work.

Resting doesn't strengthen your core, teach you how to brace, or fix your programming. It just pauses the issue. To truly solve it, you have to fix the underlying mechanical failure.

The 3-Step Fix for a Stronger, Safer Lower Back

Instead of avoiding lower back work, you need to approach it intelligently. The goal is to build a resilient back that can handle heavy loads, not to wrap it in cotton wool. Follow these three steps to build a bulletproof lower back.

Step 1: Manage Your Weekly Volume

Your lower back muscles (erector spinae) are postural muscles; they're designed for endurance. They don't need a ton of direct volume to grow and get stronger. The majority of their work comes from stabilizing your torso during heavy compound lifts.

Here’s how to manage your volume correctly:

- Indirect Work: Count your heavy sets of squats, deadlifts, bent-over rows, and standing overhead presses. This is the foundation of your back strength.

- Direct Work: This includes exercises where the primary mover is the lower back, like back extensions (hyperextensions), good mornings, and reverse hypers.

The Rule: Limit your *direct* lower back work to a maximum of 2 exercises per week. For each exercise, perform 2-3 hard sets in the 8-15 rep range. This means you are only doing 4-6 total direct sets for your lower back in an entire week. For 99% of people, this is more than enough to stimulate strength gains without causing overuse injuries.

Step 2: Master the Abdominal Brace

This is the most important skill for protecting your spine. A proper brace turns your torso into a rigid, unmoving cylinder, transferring force through your hips and legs instead of your spine. Forgetting to brace is like trying to lift a heavy box with a wet noodle for a spine.

Here's how to do it:

- Stand up straight and take a deep breath into your stomach, not your chest. Imagine filling your entire waistline with air, pushing out 360 degrees.

- Now, without letting the air out, tense your abs as if you're about to take a punch to the gut. You should feel your abs, obliques (sides), and lower back muscles all tighten simultaneously.

- Hold this tension throughout the entire repetition of a lift. Only exhale and reset at the top of the movement.

Practice this with a bodyweight squat. You will immediately feel how stable your torso becomes. This, not a lifting belt, is your primary defense against back injury.

Step 3: Build Your Core Foundation

Your lower back is overworking because the surrounding muscles are slacking. You need to strengthen the entire core unit so the load is distributed evenly. Add these three exercises to your routine 2-3 times per week.

- Plank: Focus on perfect form. Squeeze your glutes and abs. Don't let your hips sag. Aim to build up to a solid 60-second hold.

- Side Plank: This targets the obliques, which are critical for preventing your torso from twisting under load. Build up to 30-45 seconds per side.

- Dead Bug: This teaches you to keep your core braced while your limbs are moving-exactly what you need during a squat or deadlift. Aim for 10-12 slow, controlled reps per side.

These aren't glamorous exercises, but they are the foundation upon which all heavy lifting is built. Do them consistently, and your lower back will thank you.

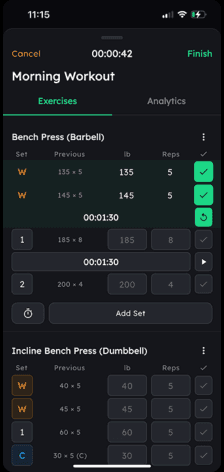

Your progress. Tracked and proven.

Every set and rep logged. See your back get stronger, safely.

Available on iOS and Android

What to Do When You Feel That Twinge

It's going to happen. You're in the middle of a heavy set, and you feel a sudden, sharp "twinge" in your lower back. How you react in the next 10 seconds determines whether it's a minor incident or a major injury.

In the Moment: Rack the Weight.

Your first and only job is to safely end the set. Do not try to push through and finish the rep. Do not drop the weight recklessly. Rack it, take a step back, and breathe. The adrenaline will be pumping, but you need to calm down and assess.

In the Next 60 Seconds: Assess the Pain.

Walk around a little. How does it feel? Is it a sharp, localized pain you can point to with one finger? Does it radiate down your glute or leg? If the answer is yes to any of these, your workout is over. Don't be a hero. Don't try to switch to an upper body exercise. Go home. Pushing through a potential spinal injury is the single dumbest thing you can do in a gym.

If the pain is more of a diffuse, dull ache-like a sudden muscle cramp-you may be okay. But your heavy lower-body work for the day is still done. You can switch to a machine-based exercise or something that doesn't load the spine, but be extremely cautious.

The Next 48 Hours: Monitor and Test.

Pay close attention to how the area feels. If the pain gets worse, stays sharp, or you develop radiating symptoms, it's time to take it seriously. However, if it calms down into a dull soreness that feels better over the next two days, you likely just had a minor muscle strain.

When to Return: The Pain-Free Test.

Do not go back to heavy lifting until you can pass these two tests with zero pain:

- Bend over and touch your toes.

- Perform 10 bodyweight squats with perfect form.

When you do return, leave your ego at the door. Start with just the bar or around 50% of your previous working weight. Focus every ounce of your mental energy on your setup and your abdominal brace. Your goal isn't to lift heavy; it's to complete every rep perfectly and prove to yourself that the movement is safe again.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many days a week should I train my lower back?

Directly train your lower back just 1-2 days per week. It receives significant indirect work from compound lifts like squats, deadlifts, and rows. Over-training it with too much direct isolation work on top of that is a common cause of strain.

Are deadlifts bad for your lower back?

No, deadlifts with proper form are one of the best exercises for building a strong, resilient lower back. They become dangerous when you use too much weight, causing your form to break down and your spine to round. Ego lifting, not the exercise itself, is the problem.

Should I wear a lifting belt?

A lifting belt is a tool to enhance a brace you already know how to perform; it is not a substitute for a strong core. Learn to brace properly without a belt first. Use a belt only for your heaviest sets, typically anything over 85% of your one-rep max.

What's better for lower back, hyperextensions or good mornings?

Beginners should start with 45-degree back extensions (hyperextensions). They offer more stability and are easier to control. Good mornings demand perfect hip hinge mechanics and can place significant shear force on the spine if done incorrectly. Master the extension before even attempting a good morning.

Can I just do planks and crunches to strengthen my lower back?

Planks are fantastic for core stability. Crunches, however, only work one part of your abs and do very little to support the spine. A balanced core program must include anti-extension (planks), anti-rotation (Pallof presses), and anti-lateral flexion (side planks) to build true 360-degree strength.

Conclusion

The fear around lower back pain is valid, but the solution is simpler than you think. It's rarely about working your back "too much" and almost always about working it *improperly* due to a weak core and a poor brace.

Stop resting and hoping the problem goes away. Start building a stronger core and mastering the brace today.

All content and media on Mofilo is created and published for informational purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition, including but not limited to eating disorders, nutritional deficiencies, injuries, or any other health concerns. If you think you may have a medical emergency or are experiencing symptoms of any health condition, call your doctor or emergency services immediately.